Heading Sub Heading

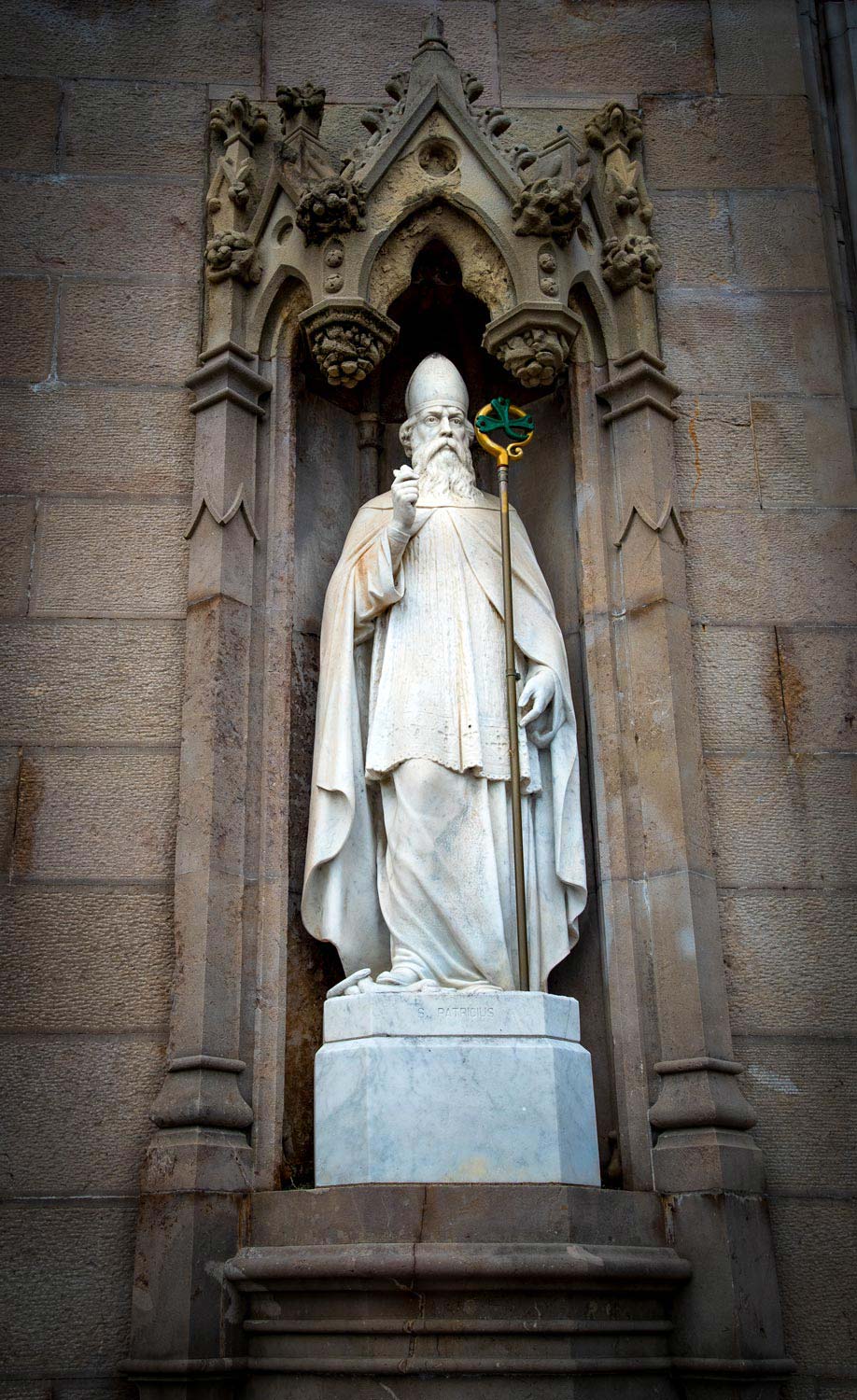

Patricius, better known as Patrick, is remembered today as the saint who drove the snakes out of Ireland, the teacher who used the shamrock to explain the Trinity, and the namesake of annual parades in New York, Boston and many cities around the world.

The year was around 430AD and the Roman army had long since left Britain to protect Rome from Barbarian invasions. Patricius and his town were unprepared for an attack by Irish warriors. Wearing helmets and armed with spears, they quickly demolished the village. As Patrick darted among burning houses, he was caught. The barbarians dragged him aboard a boat bound for the east coast of Ireland.

On arrival in Ireland, Patrick was sold to a cruel warrior chief. While Patrick minded his master’s sheep in the nearby hills, he lived like an animal himself, enduring long bouts of hunger and thirst. Worst of all, he was isolated from other human beings for months at a time.

Early missionaries to Britain had left a legacy of Christianity that young Patrick was exposed to and took with him into captivity. He now turned to the Christian God of his fathers for comfort.

“I would pray constantly during the daylight hours,” he later recalled. “The love of God and the fear of him surrounded me more and more. And faith grew. And the spirit roused so that in one day I would say as many as a hundred prayers, and at night only slightly less.”

After six years of slavery, Patrick received a supernatural message. “You do well to fast,” a mysterious voice said to him. “Soon you will return to your homeland.” Before long, the voice spoke again: “Come and see, your ship is waiting for you.” So Patrick fled and ran 200 miles to a southeastern harbour. There he boarded a ship of traders, probably carrying Irish wolfhounds to the European continent.

After a three-day journey, the men landed in Gaul (modern France), where they found only devastation. Goths or Vandals had so decimated the land that no food was to be found in the once fertile area. “What have you to say for yourself, Christian?” the ship’s captain taunted. “You boast that your God is all powerful. We’re starving to death, and we may not survive to see another soul.”

Patrick answered confidently. “Nothing is impossible to God. Turn to him and he will send us food for our journey.” At that moment, a herd of pigs appeared, “seeming to block our path.” Though Patrick instantly became “well regarded in their eyes,” his companions offered their new-found food in sacrifice to their pagan gods. Patrick did not partake.

Many scholars believe Patrick then spent a period training for ministry in Lerins, an island off the south of France near Cannes. But his autobiographical Confession includes a huge gap after his escape from Ireland. When it picks up again “after a few years,” he is back in Britain with his family.

It was there that Patrick received his call to evangelize Ireland—a vision like the apostle Paul’s at Troas, when a Macedonian man pleaded, “Help us!” “I had a vision in my dreams of a man who seemed to come from Ireland,” Patrick wrote. “His name was Victoricius, and he carried countless letters, one of which he handed over to me. I read aloud where it began: ‘The Voice of the Irish.’ And as I began to read these words, I seemed to hear the voice of the same men who lived beside the forest of Foclut … and they cried out as with one voice, ‘We appeal to you, holy servant boy, to come and walk among us.’ I was deeply moved in heart and I could read no further, so I awoke.”

Despite his reputation, Patrick wasn’t really the first to bring Christianity to Ireland. Pope Celestine I sent a bishop named Palladius to the island in 431 (about the time Patrick was captured as a slave). Some scholars believe that Palladius and Patrick are one and the same individual, but most believe Palladius was unsuccessful (possibly martyred) and Patrick was sent in his place.

In any event, paganism was still dominant when Patrick arrived on the other side of the Irish Sea. “I dwell among gentiles,” he wrote, “in the midst of pagan barbarians, worshipers of idols, and of unclean things.”

Demons and druids

Patrick did not require the native Irish to surrender their belief in supernatural beings. They were only to regard these beings in a new light as demons.

The fear of the old deities was transformed into hatred of demons. If Christianity had come to Ireland with only theological doctrines, the hope of immortal life, and ethical ideas—without miracles, mysteries, and rites—it could have never wooed the Celtic heart.

Predictably, Patrick faced the most opposition from the druids, who practiced magic, were skilled in secular learning (especially law and history) and advised Irish kings. Biographies of the saint are replete with

stories of druids who “wished to kill holy Patrick.”